Foundations of Modern Application Development Practices

Product Validation

VMware Tanzu Labs

There are a lot of unknowns when building a new software system, including customer unknowns such as product/market fit, business unknowns such as addressable market size, and technical unknowns such as how feasible something is to build.

For decades, management practice has emphasized planning and control as a means of ensuring predictable output, but building software has inherent complexities that make this management style too rigid. This rigidity is expressed in many ways, from organizations being slow to react to new information to teams not being empowered to act autonomously and react effectively to customer feedback.

One way to mitigate the risk of unknowns derailing a product or initiative is to follow the Build, Measure, Learn cycle detailed later in this article. Scientists and engineers have been using something similar known as the scientific method for at least 200 years. Both methods use data to inform decisions and place an emphasis on facts over assumptions. You can learn more about the Build, Measure Learn cycle from the book, “Lean Startup” by Eric Ries. While the book and this article use startups in several examples, the principles of lean software product development are applicable to organizations of any size and age.

What you will learn

In this article, you will learn to:

- Define assumptions and how to identify them.

- Recognize how validation can reduce risk in product development.

- Describe the Build-Measure-Learn cycle, its importance, and how each step informs the other.

- Define hypothesis, test, and validation criteria.

Define assumptions and how to identify them

Assumptions are things we believe to be true but are not verified by facts or evidence. Identifying assumptions early will help determine the questions we need to answer with research. If we do not identify and address our assumptions, we may make uninformed decisions about the product’s direction.

Assumptions introduce risk for several reasons:

- Assumptions lead to waste, which is anything that does not add value for the end user. For example, building features that customers don’t actually need requires support for what’s built, and prevents the team from building those features that customers do need.

- Assumptions are attractive and seem like facts. It’s easier to accept an assumption than it is to challenge it. For example, it’s easy to accept an assumption when it’s a commonly shared belief on your team.

- Assumptions preclude learning from customers. A team that shares assumptions about customers will not see a need to connect with those customers to learn about their needs.

To identify assumptions, run an Assumptions Exercise. You can use the output from this exercise to generate ideas for tests to run that ensure we’re building the right product. The goal is to discover assumptions, then target the ones that pose the greatest risk to our business.

An Assumptions Exercise is a simple way to:

- Identify the assumptions.

- Prioritize the assumptions that pose the greatest risk to the business.

- Set up a conversation about what research the team needs to do to validate and de-risk the assumptions.

Recognize how validation can reduce risk in product development

According to Harvard Business School, as many as 95 percent of product launches fail. Many of these failures can be attributed to flawed assumptions about user needs. You must validate assumptions about what customers really need and meet those needs with as little time, effort, and resources as possible.

Customer feedback is vital during product development. It ensures that we’re not building products that customers don’t want. The lean product development approach also borrows from the scientific method; it assumes we don’t know something to be true unless we gather the evidence to validate our belief.

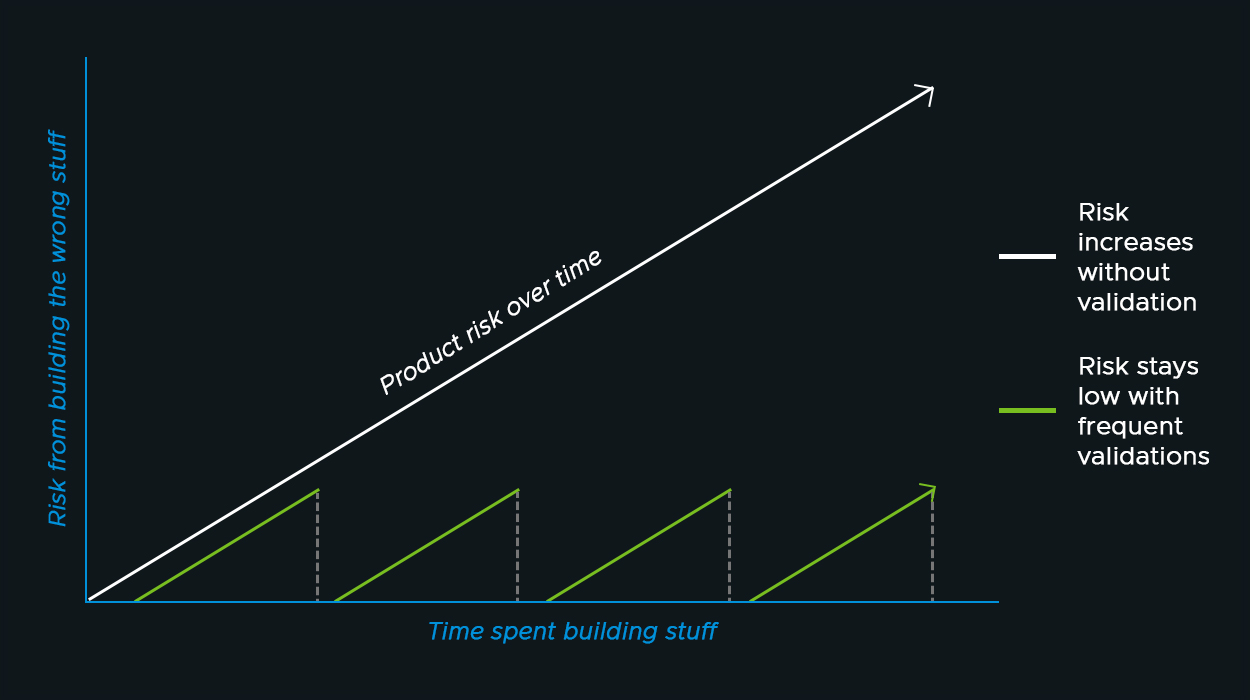

By validating our product decisions early and continuously as we build a product, we receive two important signals. First, we get an indication that we’re on the right track – that this product meets our customers needs. Second, we learn about flaws in our product so that we can change course before they become too deeply ingrained to be easily fixed.

it is especially important to get these signals early on in the development process; before we run out of money, before we put together a “big bang” product launch, or while we can still make changes cost-effectively. Validation reduces risk through explicit, focused learning cycles.

Describe the Build-Measure-Learn cycle, its importance, and how each step informs the other

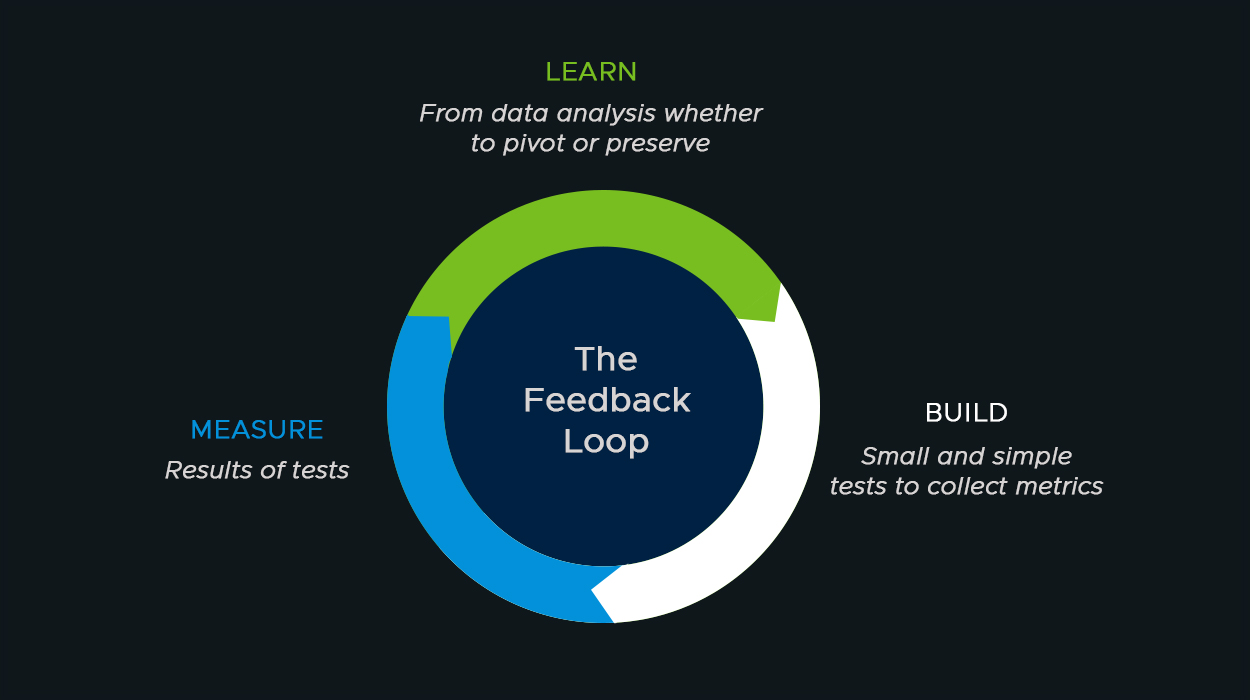

Eric Ries popularized Build-Measure-Learn as a way to identify and reduce risk, focus resources on the right work, continuously learn about our customers, and eventually build a successful product or business. This process won’t help a team succeed if it’s done once in the early days of a project. It must underpin the work the team does week-after-week. Eventually, as the team repeats the Build-Measure-Learn cycle, validated learning and a focus on outcomes will replace big ideas and a focus on output.

Although the team’s activities happen in the build, measure, and learn order, planning actually works the other way around.

First, the team needs to discover what they must learn. Next, how to measure those learnings. Organizations which do not have a history of traditional metrics, such as revenue or market share, might rely on innovation accounting. More established organizations might have traditional metrics. Regardless, it is important for all organizations to focus on the right metrics - those that impact the business. Too often, teams get stuck chasing vanity metrics, or metrics which look important on the surface, but which ultimately don’t explain performance of the business. Build-Measure-Learn helps teams at every stage focus on the right product initiatives that impact those metrics that matter to their customers and the business.

Finally, the team will figure out what must be built, based on this learning.

Build

In order to successfully run an experiment and learn from it, there needs to be something to test. For example, we can test working software. However, there are a number of lower fidelity - and lower cost - options available that the team can learn from. The team could opt to build a paper-prototype, marketing website, or a demo video and put it in front of a target audience to gain insight into how they use it.

The Build phase generally comes from questions like “what?” and “for whom?”

- What will we build?

- Who is our target persona?

- What part of this product are we most worried about?

- What’s the smallest release that will support our business outcomes?

- How can we get the most confidence for the least investment?

Measure

It’s not enough to say “we think customers will like this feature.” Instead, it’s important to anticipate (before you build) and assess (when you’re done) the impact that a feature or product has on the metrics that define your business when it is in the hands of real users.

Measures can generally be identified with questions like “why?” and “what will have changed?”

- What outcomes are we aiming for?

- How can we measure our progress towards these outcomes?

- What tracking needs to be in place so we can measure success?

- How often / When will we measure?

Learn

Learn consists of questions like “What next?” and “How does this impact our plans?”

- What do we think we will learn?

- What might lead us to decide to continue building on what we built here?

- What might lead us to decide that we should scrap what we built and revisit the suitability of the team and the process, in driving towards our desired outcomes?

- If our hypothesis is correct, what do we do next?

By measuring the impact that a certain feature has on our business, we can determine where to invest our resources next.

Define hypothesis, test, and validation criteria

The hypothesis is a falsifiable version of our assumption. We learn from the outcome of our hypothesis. Only test one variable or idea in each hypothesis. Otherwise, you won’t get reliable data because you won’t be able to tell which of the variables led to a particular outcome.

“We think X change/feature will impact Y metric in Z way for a certain group of users.”

The test is how we intend to validate our hypothesis, proving it to be true or false. The test is the thing you will build.

“To test this hypothesis we will put this feature/product/prototype in front of some segment of users.”

Test examples:

The validation criteria is the evidence that proves the hypothesis. This is what we measure.

“We will know if we were successful if this business metric has moved by X% by the end of our test.”

Business metric examples:

- Net Promoter Score

- Usability test outcomes

- Revenue per transaction

- Signed letter of intent

- New sales leads

Here is an example of a hypothesis, a test, and the validation criteria for a hypothetical video baby monitor app seeking to expand their market share.

“We believe that allowing parents to share clips of their children with friends from the video monitor will lead to a significant usage of the share feature and exposure to new potential customers.”

“We will run an A/B test and deliver a Share feature to half of our “recording-happy” user segment for 16 weeks.”

“We will know if we were successful if we see an average of one clip shared per household, per week in the test group.”

This is a relatively low-risk test that will give them a lot of confidence as to whether their customer will benefit from the proposed feature.

In this article, you learned to:

- Define assumptions and how to identify them.

- Recognize how validation can reduce risk in product development.

- Describe the Build-Measure-Learn cycle, its importance, and how each step informs the other.

- Define hypothesis, test, and validation criteria.

Keep Learning

- The Lean Startup: How Today’s Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses by Eric Ries.

- The Startup Way: How Modern Companies Use Entrepreneurial Management to Transform Culture and Drive Long-Term Growth by Eric Ries.

- Measure What Matters: OKRs: The Simple Idea that Drives 10x Growth by John Doerr.